Writing Assessment

The Arizona General Education Curriculum (AGEC) at AWC assumes that all undergraduate students will develop the intensive writing and critical inquiry skills essential to clearly reason and communicate through the medium of language. Arizona Western College believes writing provides a unique opportunity to learn disciplinary content while mastering writing skills. All English and Writing Intensive (WI) courses directly address these central institutional and cultural values.

Arizona Western College has taken multiple steps to approve student writing. In 2013, AWC stepped away from 'Writing Across the Curriculum' and to 'Writing Intensive (WI) Courses' to ensure that students have the basic academic writing skills necessary to meet the demands of a WI course. Then, in the spring of 2017, the Writing Curriculum Committee shifted the focus one more time from 'Writing Intensive' courses to 'Writing in the Discipline'. The English Department has also worked diligently to revise the developmental and composition English course curriculum to improve student writing.

If you’d like the full report of writing assessment activity in both Writing Intensive and First Year Composition, please see the HLC 1C 3B Report.

Want more information on Writing Intensive?

The steps Arizona Western College has taken to improve student writing:

WI Assessment Timeline

Arizona Western College utilized three different assessment methods from 2003-2012. Each modification in the assessment process was designed to better assess student writing.

- 2003 - 2011 - 500 word writing essay assessed through Testing Services.

- 2007 - 2012 - Writing intensive assessed via embedded writing.

- 2009 - 2012 - Assessed writing samples of students with 50 or more credit hours who successfully completed ENG 101.

In 2013, Arizona Western College determined the most appropriate assessment method was to assess student writing in designated writing courses.

- 2013 - 2017 - Writing intensive assessed in 'Writing intensive' courses. In 2017 the focus was shifted from 'Writing Intensive' courses to 'Writing in the Discipline'.

- 2017 - 2019 - Writing assessed in discipline specific writing courses.

- 2020 - Present - Writing intensive student learning outcomes (SLO) assessed (pilot) through metacognitive Phase II Portfolio Review.

Results

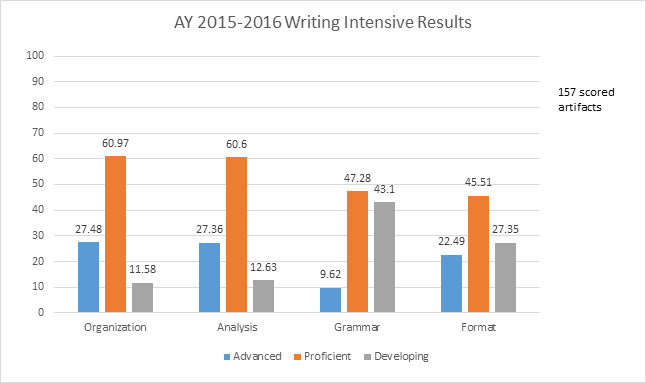

2015 - 2016 - Utilizing a scoring rubric from 1 to 3 with a score of 2 being considered proficient.

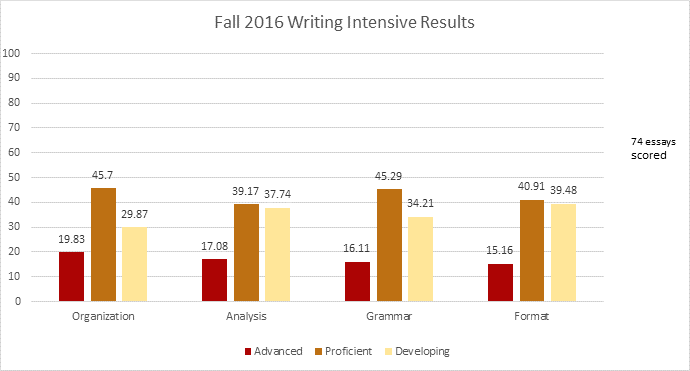

2016 (Fall only) - Utilizing a scoring rubric from 1 to 3 with a score of 2 being considered proficient.

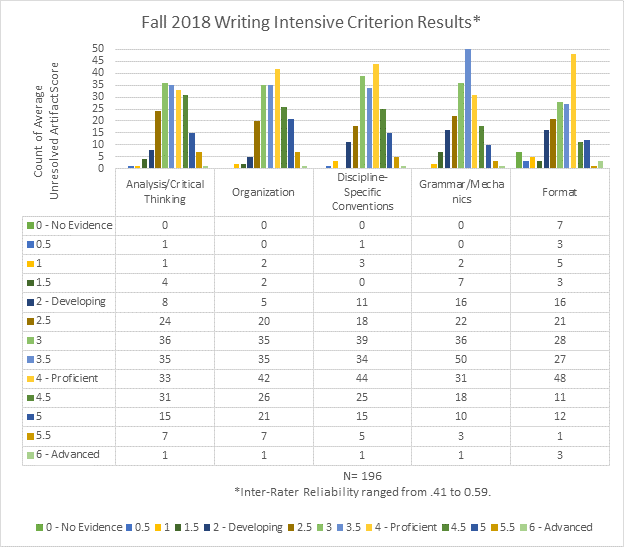

2018 (Fall only) - Artifacts scored using a 6-point rubric, condensed to three points: 5-6=Advanced; 3-4=Proficient; 1-2=Developing

*Inter-rater reliability ranged from 0.41 to 0.59. An acceptable inter-rater reliability score in the social sciences and humanities is .8 or above.

**Scores reported are unresolved.

In the Fall of 2018, the WCC pursued an assessment design that they had conducted in years before, which included a random sampling (generated by the IERG) of five students’ artifacts from each WI course being rated by the 10 WCC faculty. All WI professors participated in sending WI artifacts from the random sample provided by IERG. Three artifacts were used to norm the rating team. The rating team consisted of 10 professors and staff who serve on the Writing Curriculum Committee. Each rater had a differing background of expertise and had been nominated to represent their area in the conversation about writing on campus. Each rater rated 40 artifacts using a common rubric. Although the results should be read with the low IRR scores in mind, ultimately, this assessment showed that AWC WI students were “Less than Proficient” in each of the five criteria, which are not an exact match to the SLOs. None of this data was descriptive enough to feed back into the program.

Snyder, an expert in writing program assessment, revised the Writing Intensive assessment to be a Phase II Portfolio Review (White, Elliott, & Peckham, 2015) focusing on a common metacognitive assignment in which students demonstrate their explicit knowledge of the five Student Learning Outcomes for Writing Intensive which are:

- Demonstrate critical inquiry through the gathering, interpretation, and evaluation of evidence in writing.

- Develop flexible strategies for generating ideas, revising, editing, and proofreading, using instructor and peer feedback on written discourse to guide improvement through revision.

- Effectively compose discipline-specific writing, which includes overall organization, analysis, grammar, mechanics, punctuation, and style.

- Develop strategies for composing both in class and out of class compositions.

- Demonstrate through written discourse a sequence of increasing complexity/skill in knowledge of content as well as discipline specific discourse form.

As a course assignment, it is first graded by the instructor of record, using a mostly standardized classroom rubric and later the reflective letter portion of the course assignment is collected from all WI courses.; these artifacts then go through a Phase II Portfolio Review (White, Elliot, & Peckham, 2015) with two co-created rubrics using dynamic criterion mapping (15). The common metacognative assignment is carried out by WI faculty which is comprised of an interdisciplinary group of faculty members.

As such, the Writing Curriculum Committee developed our 3-5 Year Assessment Plan through an SLO-driven student portfolio cover letter assignment as a common metacognitive and multidisciplinary writing- about-writing essay assessment measure throughout all WI courses to promote vertical writing transfer (e.g., Melzer, 2017). The new assessment plan was ratified in the Spring of 2019 by the Writing Curriculum Committee and the pilot is underway with monetary incentives to encourage training and participation.

This pilot was funded by the VPLS and many faculty members took part in the training to administer the new pilot assessment. However, as the assessment was gaining acceptance (2020- 2022), the pandemic delayed goals, and in 2022, the AZ Transfer Steering Committee, prompted by the Arizona Board of Regents’ edict that the three state universities update their General Education curriculum, resulted in the elimination of the Writing Intensive course designation, which effectively killed all momentum for the assessment pilot. The WCC is still collecting metacognitive pilot assessment artifacts from instructors who are administering it, and a summative assessment of the pilot will take place in 2023-2024AY. The data from this assessment pilot will help the WCC focus on re-envisioning the Writing Intensive program into a robust Writing Across the Curriculum program, which will also include formative and summative assessment of student learning.

English Department 10-Year Continuous Improvement Timeline

- Spring 2009 - Every Program, course cluster, & certificate completes common assessment Matrix

- English Department Self-Study Initiated - Fall 2010 - Writing Center Opens in Student Success Center

- Spring 2011 - ENG 95+96 Assessed

- Fall 2012 - ENG 95 + ENG 96 Revised and piloted to ENG 80/90

- ENG 101 + ENG 102 Revised and Piloted based on CWPA recommendations - Fall 2013 - Revised ENG 101 + ENG 102 implemented

- Spring 2018 - ENG 100 Assessed

- Spring 2019 - ENG 101 Assessed through metacognitive Phase II Portfolio Review (pilot)

- Fall 2021 - ENG 101 Assessed through metacognitive Phase II Portfolio Review (pilot)

- Fall 2022 - ENG 101 Assessed through metacognitive Phase II Portfolio Review (pilot) Pilot status revocation in progress.

First Year Writing Program Improvement:

At the same time that the WCC was revamping their assessment, the Writing Program Administrator, Dr. Snyder, has been working with the Communications Department faculty and the First-Year Writing Program (includes pre-matriculation and matriculation-level composition courses: ENG 090, ENG 100, ENG 101, ENG 102, ENG 107, ENG 108) on a similarly robust, reliable, and valid assessment of student learning in first year composition courses—the classes that touch the most students at AWC. Starting in 2019, the composition professors co-created and started to teach a common metacognitive reflective cover letter assignment paired with an ePortfolio as an assessment pilot focusing on the Student Learning Objectives for ENG 101:

- 2.1 Analyze and address the rhetorical situations within specific discourse communities.

- 2.2 Compose for multiple purposes and multiple genres, including reflection, analysis, explanation, and persuasion.

- 2.3 Use writing and reading for inquiry, discovery, critical thinking, and communication, and to integrate their own ideas with those of others to create new knowledge.

- 2.4 Document their work using academic citation systems and formats.

- 2.5 Engage in a recursive writing process, developing flexible strategies for generating ideas, revising, editing, and proofreading.

- 2.6 Engage in and understand the collaborative and social aspects of writing.

- 2.7 Use a variety of 21st Century online composing space technologies to address a range of audiences.

- 2.8 Apply major grammatical conventions of Standard English meaningfully and accurately to written communication appropriate for college level.

The ENG101/100 co-req and ENG100/107 co-req classes create both a metacognitive reflective cover letter and an e-Portfolio. The construction of the metacognitive reflective cover letter requires the students to use the course outcomes of the ENG 101/107 syllabus as a road map to metacognitively analyze their own progress and learning throughout the course. They are required to use the same language of the text and provide examples of their own writing within the essay to demonstrate to the professor, as well as themselves, what they have learned. They make a claim whether they have met the specific course outcomes; provide evidence of how they have met the course outcomes; explain why that evidence is a good example of the course outcome and their learning; and finally speculate how they will use the course outcome in future contexts to encourage transfer of skills. In this fashion, we assure that the bases for evaluation cohere with the programmatic goals with both student and professor. This also ensures that we are consistent in the evaluation of students' writing as a department for this endeavor.

The primary means of evaluating student success in SLOs is through the metacognitive portfolio “Cover Letter,” a shared assignment, standardized across all sections of ENG-101/ENG-107 and ENG-102/ENG-108, which is included as part of the larger shared ePortfolio assignment, also used in all sections. In the Cover Letter, students are instructed to follow a specific template in which they write several paragraphs, one for each of that course’s SLOs. In each paragraph, students follow four moves in which they state mastery of the SLO, self-quote from their work

for the semester to demonstrate that mastery, explain how the self-quote demonstrates mastery, and finally apply that mastery by explaining how they can use the skill described in the SLO in the future. Faculty subsequently evaluate a random and de-identified set of Cover Letters and determine, using a shared summative and a shared formative rubric, the extent to which mastery of the SLO skills has been demonstrated. Some faculty members do additional work throughout the semester to prepare students for this process, such as having the students review the SLOs throughout the semester and assignment regular short reflections throughout the semester that tie specific assignments to SLOs. Faculty members work to align their assignments to the SLOs and make other efforts to align their course content and assignments to best achieve the goals represented by the SLOs.

The first round of data was collected in AY 2019-2020, analyzed in Spring 2020, and results are still being acted upon as of this writing (2023 Spring).

Method:

The Communications Division underwent a pilot study of the new assessment plan for the Spring of 2018-2019. Students wrote tailored essays giving evidence for how they met each of the eight student learning outcomes for ENG 101. In August 2019, 22 professors came together with Dr. Edward White, an expert in writing assessment, and normed to the following 6-point formative and summative rubrics which were made in Spring 2019 with the Co-Req faculty through Dynamic Criterion Mapping (Broad, 2003) techniques.

Results:

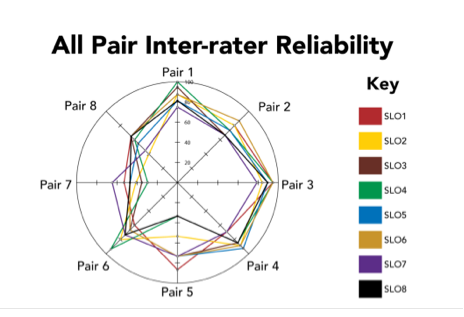

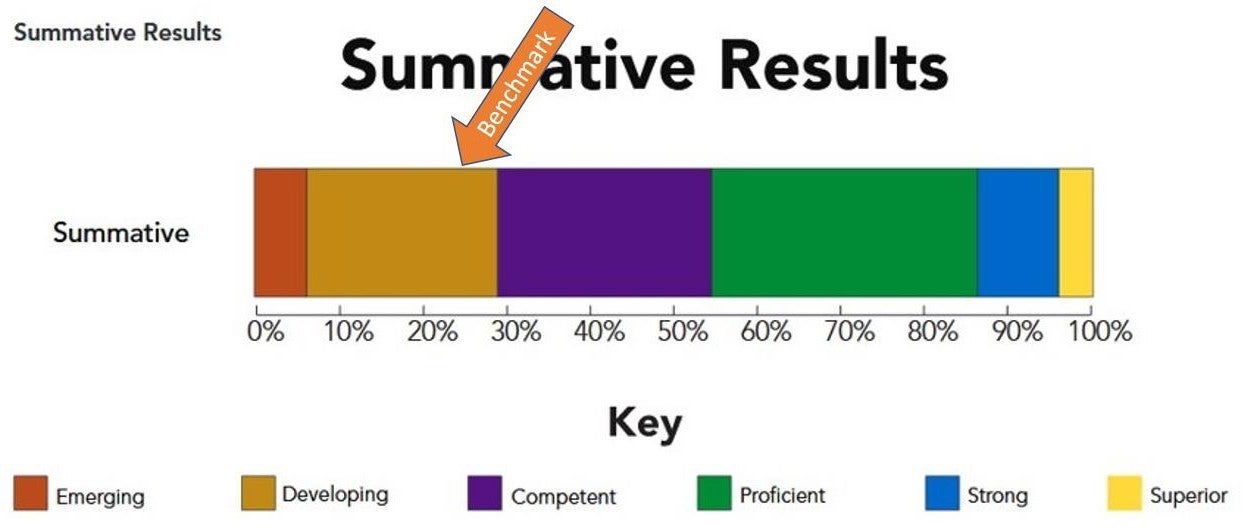

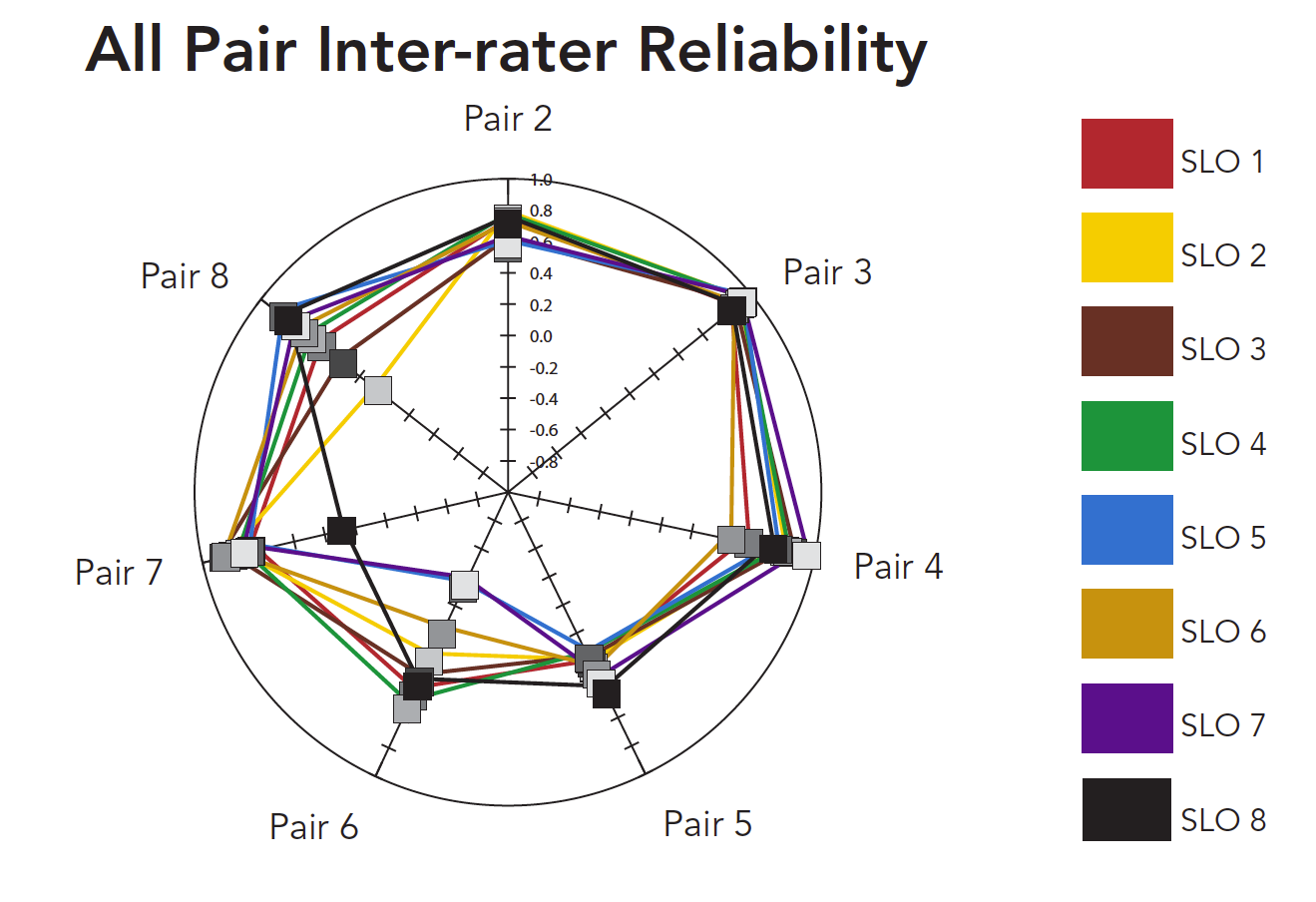

All results of the assessment should be read with IRR in mind, which for this first round of Phase II Portfolio Review, using two new rubrics with an hour and a half norming session and a new common assignment, ranged between .67 to .80 which is a marked improvement from the previous Writing Intensive assessment design (.41-.59). This range is also a promising level of agreement for the first time that the assessment has been conducted. Inter-rater reliability is expected to become higher with future iterations of this assessment. Each professor was given 20 artifacts and two weeks to finish the rating. The radar chart below visualizes that rater pairs 5, 6, 7, and 8 were not using the rubric in the same manner, but pairs 1, 2, 3, and 4 were, suggesting that more norming is needed.

The summative results show that just over 70% of our students are “Competent” or above when their metacognitive essay and eportfolio are rated in the Phase II Portfolio Review. The benchmark that the Communications department set as a goal was 75%.

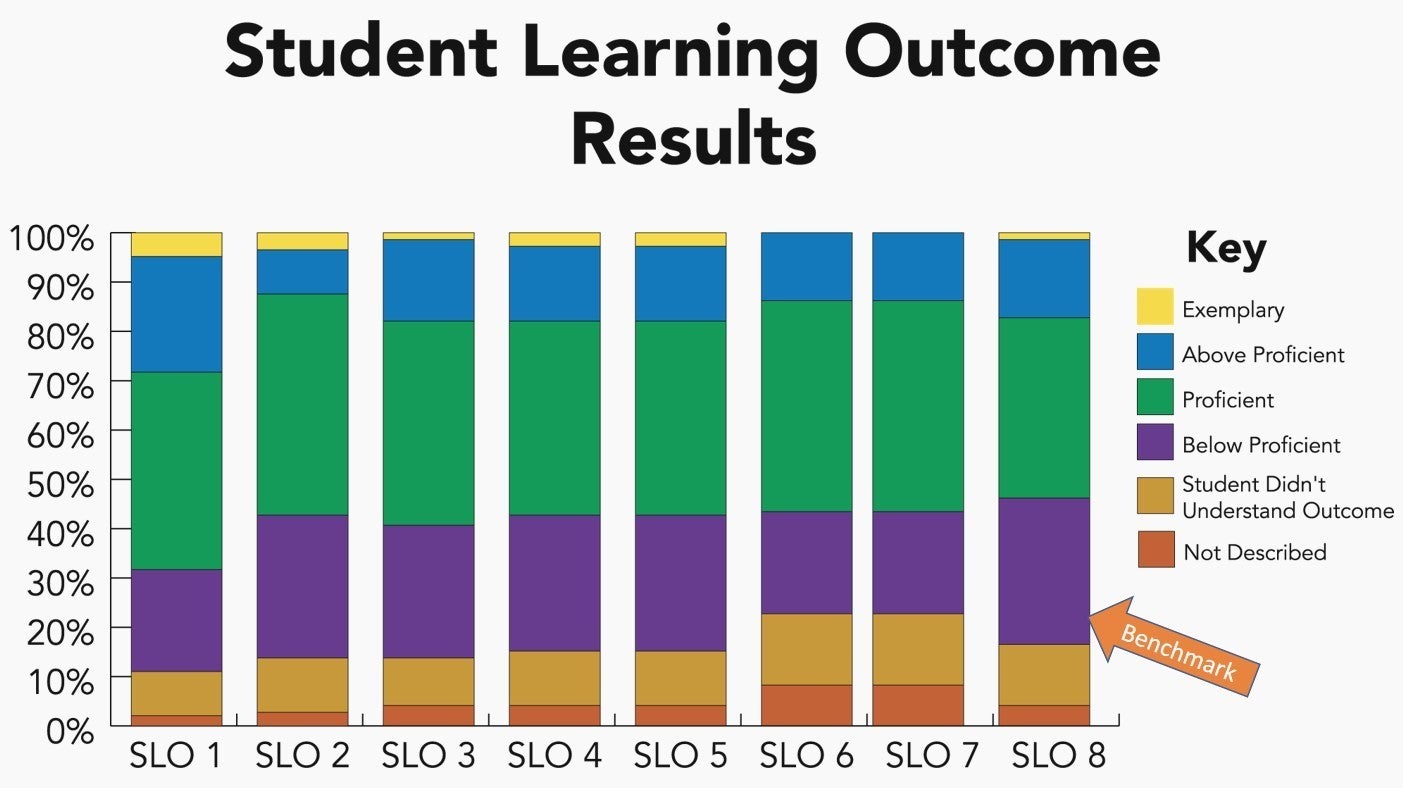

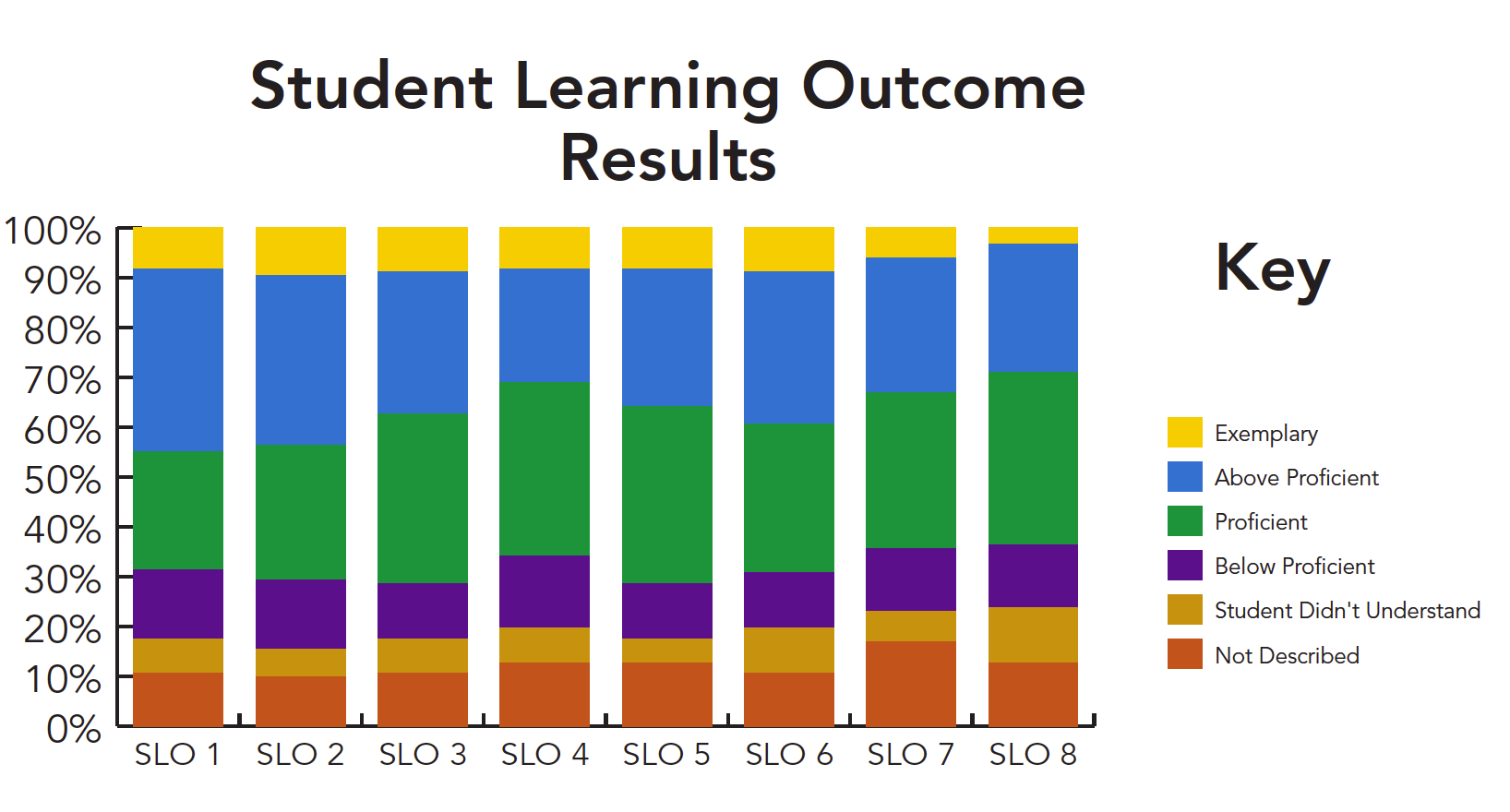

The Student Learning Outcome Results (formative) show that no students are exemplary in SLOs 6 and 7, but that there are about 60% of students who are proficient in each SLO. These results give us room to improve through understanding what students need in our qualitative analysis.

The qualitative analysis of each SLO includes all composition faculty sampling student writing about each SLO from the metacognitive essay in each score category and asking the following questions:

- What are students doing well in this SLO?

- What portion of the student learning outcome are students not writing about from this SLO?

- What misunderstandings do students seem to be having about this SLO?

- Are there any other patterns of student (mis)understanding that aren’t represented in these samples? What are they and how are they significant?

- Based on this analysis of the SLO, what recommendations might this group put forward to the Division to feed back into the program? (Remember to make S-M-A-R-T goals)

- Specific (simple, sensible, significant)

- Measurable (meaningful, motivating)

- Achievable (agreed, attainable)

- Relevant (reasonable, realistic and resourced, results-based)

- Time bound (time based, time limited, time/cost limited, timely, time sensitive)

The formative analysis of this reflective SLO letter assignment also made it clear that students struggled with the verbiage of the ENG 101 SLOs, and we discovered a sense of confusion over certain terminology, such as genre. Over the course of several semesters, a taskforce of English professors convened to workshop the ENG 101 SLOs to make them more accurate and streamlined for both student and instructor. After much discussion and revision, a preliminary survey was presented to the Communications department in Spring 2022.The results of that survey yielded these results over the preferred verbiage of the ENG 101 SLOs:

| Summary | Original SLO | Option 1 (Minimal change but perhaps quickly outdated) | Option 2 (Optimal Change, current with the field) | Option 3 (Future-looking Change, connected to PD) |

| Audience/Rhet orical Situation | 2.1 Analyze and address the rhetorical situations within specific discourse communities. | 2.1 Analyze and apply the rhetorical situations for specific audiences. | 2.1 Make writerly choices based on different rhetorical situation(s). | |

| Genre Awareness/ Genre-Specific Knowledge | 2.2 Compose for multiple purposes and multiple genres, including reflection, analysis, explanation, and persuasion. | 2.2 Compose for multiple genres and multiple purposes including reflection, analysis, explanation, and persuasion. | 2.2 Demonstrate genre awareness and genre-specific knowledge to compose in multiple genres. | |

| Critical Thinking/ Research to Problem Solve | 2.3 Use writing and reading for inquiry, discovery, critical thinking, and communication, and to integrate their own ideas with those of others to create new knowledge. | 2.3 Use writing and reading for inquiry, discovery, critical thinking, and communication, and to integrate their own ideas with those of others. | ||

| Citation Styles | 2.4 Document their work using academic citation systems and formats. |

|||

| Writing Process | 2.5 Engage in a recursive writing process, developing flexible strategies for generating ideas, revising, editing, and proofreading. | |||

| Collaboration as Writers | 2.6 Engage in and understand the collaborative and social aspects of writing. | 2.6 Communicate and collaborate with peers in order to engage in the social aspects of writing. | 2.6 Collaborate with peers to engage in the social aspects of writing | |

| Multimodal Composition | 2.7 Use a variety of 21st century online composing space technologies to address a range of audiences and purposes? | 2.7 Use a variety of composting technologies to address a range or audiences and purposes. | 2.7 Compose with a variety of accessible digital modalities to effectively address a range of audiences. | 2.7. Optimize the composing environments (print and non- print) and their unique capacities. |

| (Critical) Language Awareness | 2.8 Apply major grammatical conventions of standard English meaningfully and accurately to written communication appropriate for college level. | 2.8 Apply major conventions of Academic English meaningfully to written communication appropriate for college level. | 2.8 Examine the origins, validity, and usefulness of specific prescriptive rules in specific situations | 2.8 Recognize the existence of a variety of linguistic structures, their functions, and how they influence the intersection of language and power. |

Thanks to the SLO Taskforce who met five times over the Fall 2020 semester and three more times over the Spring 2021 semester to think through the ENG 101 SLOs and their meanings for the students at AWC. Submitted on 4/26/2021 to Dr. Eric Lee, Division Chair. Taskforce members included: Paul Huggins, Trisha Campbell, Glen Piskula, Kevin Kato, Sara Amani, Jennifer Thimell, Sarah Snyder

Discussion over these revised SLOs is still ongoing in the English department, with the hope for a final vote to be carried out in Fall 2023, closing the assessment feedback loop for that first, pilot cycle of assessment.

This first round of pilot assessment was given an assessment “Kudos” from Elaine Groggett, the then Director of Assessment, Program Review, Curriculum and Articulation in January of 2020:

I would like to give a shout out to the English faculty for their assessment efforts this year!

Thanks to the leadership of Dr. Snyder and Dr. Lee, the English faculty accomplished two significant tasks. They set an ENG 101 benchmark (visit the Assessment website Institutional Benchmarks tab for more information) and they conducted a meaningful and generative assessment of ENG 101 artifacts for this year’s ENG 101 assessment plan. Even though assessment plans are not yet due, the group provided me with a sneak peek into their assessment efforts and I feel fairly comfortable saying they are looking very good for earning themselves an assessment award for 2019-2020.

Thank you for English faculty for your hard work this year and most importantly, for closing the loop to move a class that all of our students have to take at AWC from good to great! I look forward to reviewing your completed assessment plan and hope your determination to improve teaching and learning in your department encourages others to develop and or finish their assessment plans to improve teaching, learning, and services at AWC.

If you see one or more of the individuals listed below, give them the kudos they deserve for doing their part in assessment!

Sarah Snyder, Eric Lee, Troy Burns, Doug Cox, Jonathan Close, Paul Huggins, Sonja Greiner, Donna Taylor, Denise Fregozo, Jennifer Thimell, Michael Miller, Steve Moore, Ellen Riek, Ed Schubert, Kevin Kato, Sara Amani, Dave Kern, Clayton Nichols, Daniel Herrera, Ric Jahna, Ed Snook, Deb Winters, Marco Medrano, John Hessinger, Jennie Buoy, and Earl Smith

The assessment awards were indefinitely suspended the subsequent year as the institution navigated through the vicissitudes of the pandemic, underwent a substantive reorganization, and experienced a successive and quick turnover of upper leadership.

The second round of data was collected in AY 2020-2021 and rated in 2021-2022. The results below show a pair by pair inter-rater reliability measurement for each student learning outcome. This radar chart provides insights into how the variances of each SLO and how those variances differ by rater pairs. For instance, in comparison to the first round grouping of the all pair inter- rater reliability, the overall trend of the second round shows more uniform shape (average IRR of around .7). There was even a randomly assigned rater pair who achieved a .88 inter-rater reliability score. This tighter grouping by individual pairs for each SLO suggests a more effective norming session. Variance in SLOs as averages between individual raters reflects an interesting area to complement the subsequent round of qualitative analysis. For instance, when inter-rater reliability is averaged by SLO large variance offers pathways to explore the verbiage of the SLOs (as in the previous round which led to revision) as well as addressing more explicitly what our colleagues expect when reading particular keywords or ‘scare words’ in the

SLOs (cf. Costino & Hyon, 2011). X .

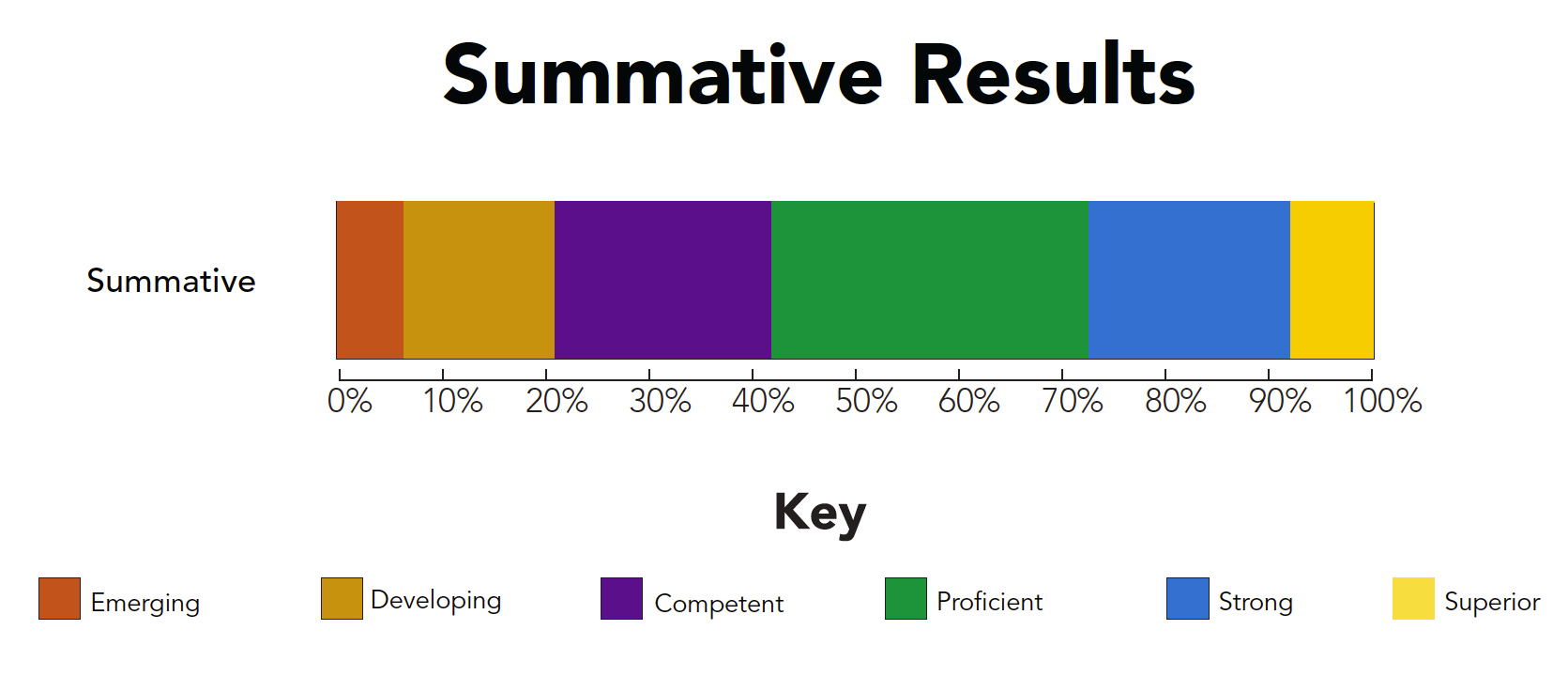

Just under 80% of our students are “Competent” or above in the summative rubric results, which reflects our raters’ observations of the students’ performance in the metacognitive essay holistically. This also shows that we have increased the quality of teaching and learning from the cycle before and have surpassed our benchmark of 75%.

In the formative rubric, raters assess each students’ understanding of the individual eight SLOs independently via the metacognitive essay and rate accordingly. One important interpretation of

this data longitudinally is that SLOs 6 and 7 are showing that students have been scored as exemplary, which didn’t happen in the first round of assessment from 2019. As the department undertook professional development to further understand those SLOs, and the rating group becomes more diverse in their understanding of the SLOs, students may show higher competencies in each SLO. Another interpretation may align with the findings of the inter-rater reliability radar chart, that as a department the tightening of variance and less skewed distribution of rating on individual SLOs may have been born of a better and more reliable norming session.

Both summative and formative data feed back into our program assessment to improve student learning. Further analysis of the summative results combined with artifact text sampling to provide a qualitative analysis that will feedback formatively into the program is scheduled for all composition faculty in AY 2023-2024.

In Spring 2023, first year composition faculty were invited to four “Assessment Share Out” sessions to evaluate the experience with the assessment pilot assignments and to collaborate to revise the assessment to use our assessment pilot program experiences to create a shared assessment that we are proud of, enjoy, and that meets our formative and summative assessment needs. This process of assessment revision and recreating the culture of assessment at AWC in the first-year composition program is ongoing, and we anticipate having a permanent, shared, metacognitive assessment of student learning objectives built into the curriculum. We hope to be able to showcase student learning and engagement through these ePortfolios and their metacognitive learning projects in a campus-wide digital portfolio system in the future.